I agree in many respects with the tenets of Copenhagen Cycle Chic, brainchild of marketing professional Mikael Colville-Andersen, which he promotes on his blog of the same name as well as in speaking tours around the world. A post from 2009 sums up his mission well: You don’t need special clothes to bicycle in, you just need to look in your own closet. It’s a much-needed message and one I admire; in fact, demonstrating that bicycling can suit your existing lifestyle and that there is no need to spend a lot of money or force yourself into some kind of athletic or rugged mold is one of the goals of my forthcoming book, Everyday Bicycling.

Unfortunately, instead of sticking to this inclusive and welcoming message, Colville-Andersen takes every opportunity to police what people choose to wear, and in an alarmingly gendered manner. Dare to take issue, and he’ll draw the line even more starkly, dismissively accusing you of factionalism, in prose peppered with ad hominem attacks (try it, you’ll see). It’s a tone reminiscent of that of the hardcore proponents of vehicular cycling: Good, common sense ideas presented in an extreme and exclusionary manner.

Helmets and technical cycling clothes are his particular targets. In the annals of Cycle Chic, to wear these things is more than a fashion faux pas, it’s socially irresponsible; a tacit endorsement of “profiteering” and a “Culture of Fear” — two of the catch phrases of which Colville-Andersen’s writing almost entirely consists.

Much of this fashion policing is directed, explicitly or implicitly, at women. “Bike advocacy in high heels” is another frequently heard catch phrase, a term which can perhaps best be understood by reading the Cycle Chic Manifesto (which comes with the slippery disclaimer that it is only partly serious): “I embrace my responsibility to contribute visually to a more aesthetically pleasing urban landscape” is one pledge, followed by “I am aware that my mere prescence in said urban landscape will inspire others without me being labelled as a ‘bicycle activist’.” Obviously these pledges could be and surely are taken to heart by both men and women, but I will submit that according to the blog’s FAQ, females apparently make up the majority of its audience, and second, that there is not exactly a rich cultural tradition of men admonishing other men to shut up and look pretty, or be seen rather than heard, or to arrange their public lives so as to be aesthetically pleasing.

Historically, in fact, Cycle Chic was all about men leering at women. It’s described by its founder in an early interview as being literally about women as aesthetic objects:

“Danish and European women just happen to be stylish. It’s elegant, it’s classy. It’s Europe. And, I’m a man. I enjoy looking at aesthetically pleasing women. If I lived in a forest, I’d probably take pictures of the nicest trees.”

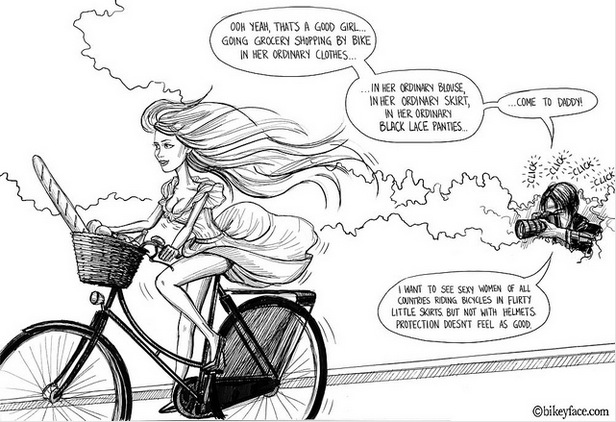

The inimitable Bikeyface has drawn the best response (used here with permission):

Colville-Andersen’s reply to this cartoon sadly illustrates some of the problems that arise in defining and critiquing his movement.

I think in part the divide between Cycle Chic’s purported message and its actual one is in the idea of what is, or should be “normal.” After all, it was perfectly normal for decades for women to value themselves and be valued for their appearance and to achieve social acceptance by catering to the aesthetic demands of male onlookers.

The world is a little more complicated now — at least it is in the United States. I recognize that gender politics in Denmark might vary, but here it is beyond tone deaf to assume that realizing you can bike without wearing Lycra is the only barrier to women embracing bicycling. In my observation, people do a pretty good job figuring that out on their own. We do, however, suffer some major economic and social barriers, from unequal division of paid and unpaid labor, to the consequences of antiquated maternity and paternity leave laws, to outright discrimination and double standards both socially and in the workplace. Barriers to bicycling are far more complicated than knowing you can bike in high heels; if that were all there was to it, we wouldn’t need a guy in Europe to come point out the solution.

Among the many who have embraced the idea (and name) of Cycle Chic for its basic tenets, not all have also taken on the tone and prejudices of its founder. It’s been a pleasure in the last few years to meet several devotees of the philosophy who have crafted it into something empowering, playful, and fun, rejecting some of the more extreme stances of the original. These folks hardly invented the practice of everyday bicycling, but they have injected a certain costumey flair into U.S. bike culture that strikes a chord with a range of people who might not otherwise get excited about cycling. This appeal is culturally specific, however, and that culture is difficult, in the U.S., to separate from the bummer stereotype of elitism. I don’t think that’s a reason not to dress chic on a bike; I do think it’s foolish to claim that it’s the highest form of advocacy in a cultural and economic situation where bicycling is falsely viewed, and subsequently de-funded, as an upper class leisure activity.

I hypothesize that Cycle Chic’s true message and appeal is at its base, at least in North America, that it seeks to normalize a gendered code of conduct that, sadly, still holds considerable appeal among both sexes. Its message is that bicycling can be a means of, rather than a barrier to, conforming to a certain set of standards of gender and class stereotypes — and access to these standards is far from universal.

In order to truly break down barriers to bicycling, it’s necessary to understand what those barriers are — which requires listening to people, rather than mocking them. It will also require, perhaps to the chagrin of Cycle Chic purists, a whole hell of a lot of activism. I don’t know about Denmark, but here in the US there’s a lot of work to be done on multiple fronts of gender parity and cycling policy, from the floors of community bike shops to the halls of Congress. Great things can certainly be achieved while wearing high heels, but never solely by doing so.

I began cycling over a decade ago wearing regular clothes and as an alternative to the bus; in more recent years, I was overjoyed to discover the wonders of the chamois and the technical cycling rain jacket. To get anthropological for a moment, here in the US, cycling for sport is one of the main avenues of entry into bicycling, and there is a vibrant, though hardly mandatory, cross-over between sports and transportation cycling. People who ride bikes in the US fall along a broad spectrum between the two, exploring and code-switching at will. Dressing up to the nines and riding fast across town on a sporty road bike are two of life’s pleasures that I find are best enjoyed jointly. Your experience may, and probably does, vary. To revert to the merely editorial: Anyone who claims that you have to choose sides, or define your style at all, is wrong, and isn’t having as much fun as you.

In summary, Cycle Chic has great potential as a movement, a potential which has been fully realized by many of its fans. It’s unfortunate, therefore, that its founder chooses instead to promote a vision of “normal, mainstream” bicycle transportation that is sexist, exclusive in many North American contexts, and unrealistic as an advocacy strategy.

I have gone to the trouble of making these points at this time, despite feeling that they are fairly obvious and an easy target, and also despite my dread of the dismissive lecturing that is sure to come my way as result, because Colville-Andersen will be headlining the fashion show component of the second National Women’s Bicycling Summit in Long Beach this September (he is also the lead keynote of Pro Walk / Pro Bike immediately prior, sharing the podium with six other men and one woman). It is an interesting time in the US, with bicycling becoming daily more mainstream, though hardly in a unitary or consistent manner, and these events are an opportunity to coordinate strategies for making the bike’s popularity stick. Fashion will surely play a part, among many other forces, and I’m looking forward to the proceedings as an opportunity for — hopefully — constructive dialogue. There’s no reason the conversation shouldn’t start now.

Note: I didn’t intend for this discussion to turn into a helmet debate, but am fine with the fact that it is beginning to. If you’re keen to discuss helmets, I recommend also heading over to this post here and its interesting comments.