Want more feminist science fiction in the world? Back Dragon Bike on Kickstarter through Nov 1, 2019!

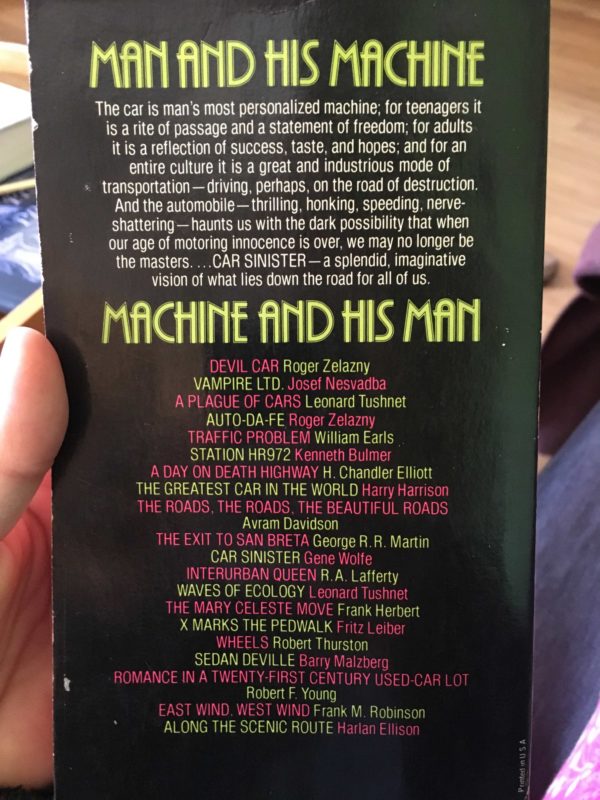

Last summer, as I was preparing the Kickstarter project for Bikes Not Rockets, my colleague Jeremy Withers, a professor of bicycle science fiction at Iowa State (sadly, I’m not 100% sure that’s his official job title), sent me an email about what may in fact be my arch-nemesis of books: Car Sinister, a long out-of-print, justifiably obscure 1979 anthology of reprinted sci fi stories from the previous two decades about cars, and by and about men.

“It has no bicycles in it,” Jeremy wrote, “but has some really imaginative depictions of cars, roads, traffic, etc. And as the title suggests, the book takes a pretty dim and dismissive view of the automobile. Most of the stories are 1960s and 1970s SF, with selections by some of the masters of that era (Roger Zelazny, Avram Davidson, Frank Herbert, Harlan Ellison, George R. R. Martin, etc.). Unfortunately, the book is also a proverbial sausage fest: no women writers!”

How could I not be delighted to find the evil mirror twin of my feminist bicycle science fiction genre? Gleefully, I ordered a used copy on the spot, and pledged to write a feminist review of it as a special reward level on the Kickstarter project. Someone stepped up to the plate (thank you!). So once the funding campaign for the next Bikes in Space book, Dragon Bike, began, I buckled down.

Nothing but spoilers to follow.

I expected this review to be a fairly easy mandate—no great nuanced reading would be necessary to find a feminist critique for these stories. And truly, I was not disappointed. Most of the stories in this book contain women as window dressing only. A meter maid, an old lady waving a sign, a girl standing in the crowd. The female characters given larger roles tend to be objects of contempt, attraction, or foils for the male lead’s grandiosity.

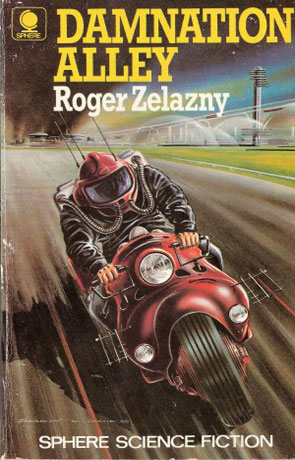

The stories that are least critical of cars are the ones steeped in the most toxic masculinity—like Roger Zelazny’s two contributions to the volume, each of which pits a stoical, solo man against against a machine. In “Auto-da-Fé,” women appear only as faceless parts of the crowd cheering on the automotive matador.

But in Zelazny’s other story, “Devil Car,” one of the two main characters is a woman, sort of. This is the very first one in the book, chosen by the volume’s three editors to set the tone and substance of the entire volume. It is the story of a man and his car, whose name is Jenny. Jenny, literally an object that he owns, nags him to take care of himself and he snaps at her. When he apologizes, her response: “‘That’s alright, Sam,’ said the delicate voice. ‘I am programmed to understand you.’”

Jenny is a sentient, state-of-the-art killing machine designed with the sole purpose of destroying the titular Devil Car. But when the moment comes, she intentionally misfires. She is simply “too emotional.” The story ends with her human cargo patting her seat and reassuring her that, despite her faults, she’s “well-equipped” and still desirable.

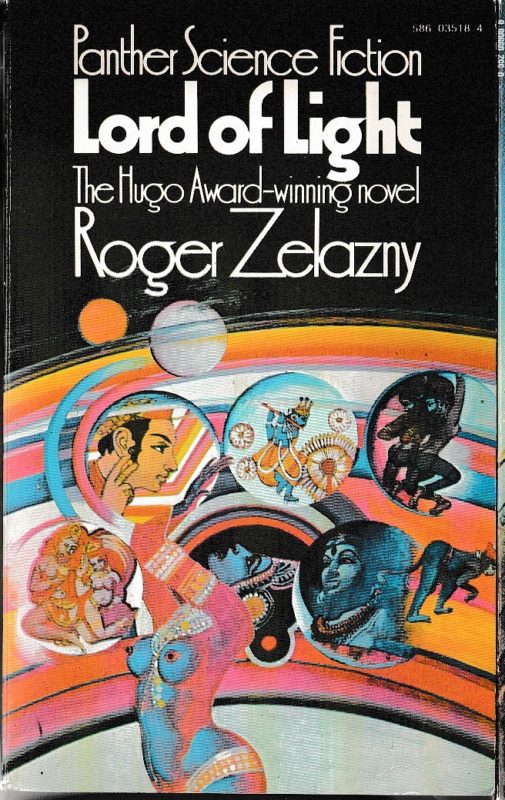

Recovering from the experience of reading this story led me down a minor rabbit hole in which I learned that Zelazny is best known for a series in which a bunch of white characters colonize a planet where they lord over the other inhabitants in the guise of Hindu gods.

(See? This review writes itself.)

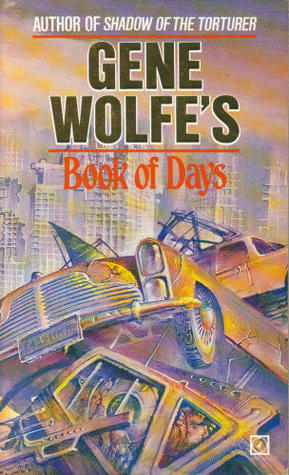

So maybe I’m feeling conspiratorial, but there is one other story in this volume in which a car is anthropomorphized as female—and it’s the book’s midway point and namesake, Gene Wolfe’s “Car Sinister.” A man takes his sports car into a shop for “servicing” and gets, um, stud service and the car becomes, as the mechanic puts it, “that way.” No woman appears for most of the story, until a passing mention in the end that after the birth, he drives the new car, and gives the old, feminized, one to his wife.

Of course, you don’t need to turn your women characters into objects to strip them of their personhood. In Harry Harrison’s “The Greatest Car in the World,” an automotive engineer travels from Detroit to Italy to drop in uninvited on his childhood hero, a race car driver, now an ailing old man. After bullying his way through the front door, he’s greeted by a girl who asks him why he is intruding in “cold tones unsuited to the velvet warmth of her voice. At any other time, Haroway would have taken a greater interest in this delightful example of female construction, but” … he takes a paragraph to describe her tresses, her bosom, and her lips, and then replies rudely and dismissively. This is pretty standard for the majority of stories in this volume. When women appear, they primarily exist as story devices, coveted but contemptible objects for the male gaze.

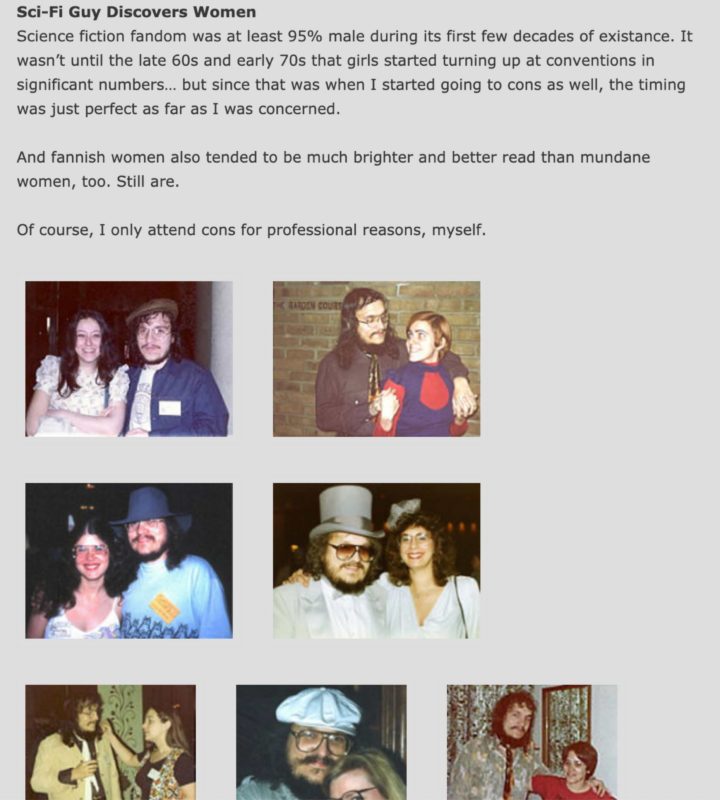

I was especially curious to read George R.R. Martin’s entry in this volume. The introduction to his story touts him as “one of sf’s brightest young stars and whose nickname is ‘Railroad.'” This sent me off on an image search for “young George R.R. Martin,” which I discovered many of on the web page he keeps about the conventions he’s been to over the years. It contains lots of photos of him, including this collection (truncated so as to include the text, which speaks a thousand pictures) of himself posing with various ladies who, unlike the people appearing in the other pre-selfie photos on this page, are unnamed:

But much as Mr. Martin seems to appreciate women, his story in this book, “The Exit to San Breta,” detailing a crash with a ghost car, is the only one in the book that contains no women at all; not even as window dressing or a passing aside. The copyright page tells us this story was written in 1971, so I guess that’s before he discovered our existence.

The other still-pretty-famous author represented here is Frank Herbert, whose Dune series tackled gender in big ways that attempted to break free from sexist stereotypes, even if it didn’t always work. Not here, though! His story is called a promisingly feminine “The Mary Celeste Move” but the only female character is secretary who appears briefly. We don’t know her name, but we do learn that she’s a “well-endowed brunette.”

Not all the stories are dehumanizing or dismissive to women. Kenneth Bulmer’s “Station HR972” is an opaquely written description of a day in the life of a futuristic service station on a high-speed (250mph) highway.

I was bemused by this passage on page one: “Libby, the torso technician for whose sake he walked the extra hundred yards for coffee, played it cool, daily less shy, daily more inclined to talk about her own handling of units and less to listen to his accounts of rapid crane manipulations.”

Libby turns out to be a skilled surgeon dedicated to rapidly putting humans back together after the inevitable high speed car crashes. She might be the most (only?) empowered woman in this book. Certainly, she’s the only one with a non-secretarial job.

There are a couple of women in whom we glimpse a more complicated humanity. In H. Chandler Elliott’s cartoonishly colloquial “A Day on Death Highway,” a nuclear family flees a planet with strict automotive safety laws to try out life in a different dimension where the dad can fully indulge his road rage and his belief that no rules should apply to him. The story’s notable because dad’s buffoonery isn’t glorified; the family dysfunction is deftly painted, and while Mom and sister Judy aren’t given a lot of ink, they clearly have their own agency and motives.

(Contrast this with the final story in the book, Harlan Ellison’s “Along the Scenic Route” which depicts in gory detail a road-rage fueled duel in which the driver’s wife cowers in the passenger seat as he escalates a violent encounter to its fatal climax … but she is the one to comfort him after they survive. “You did what you had to,” she croons. Side note, he calls another driver a “beaver-sucker,” an insult now burned into my brain.)

Perhaps best of the lot (in representation… not in writing style) was Robert F. Young’s very long and unpromisingly titled “Romance in a Twenty-first Century Used-Car Lot.” The main character is a woman! At first, we think she’s an anthropomorphized car, but then we discover this is a society where cars must be worn like clothes, or you’ll be exiled to a “nudist reservation.” Our heroine Arabella Grille lives in a sexist society, but she’s a complicated person with insecurities and strengths that we get to see played out in the story. Her appearance is equated with her value and her intellectual bent is bemoaned by her abusive family, her image-conscious workplace, and her fascist-consumerist society.

In this story, we see the impact of the behavior and attitudes demonstrated in the other stories. When a car-clad stranger, attracted to her new car-dress, bullies her into a date to the drive-in movie, she feels validated. When he tries to assault her (including grabbing her headlights and grinding his chassis against hers), she knows everyone will blame her for the crumpled fender that resulted from fighting him off. A 24 hour mechanic helps her fix it, and asks her out more kindly. They fall in love over the course of a few dates, but her attacker calls the police; they intervene and it turns out that her new love is a secret nudist! After she sees her family’s reaction, she decides to run away to the nudist reservation, too, where no cars are allowed, and they live happily ever after in a single-family detached home with a swimming pool.

Towards the end of the story, Arabella has a revelation about her would-be rapist. “He hates me because he betrayed to me what he really is, and in his heart, he despises what he really is!” This nugget of wisdom is a contender for the highlight of the book, matched only by the machine-gun wielding old lady pedestrian who manages to take out several passengers in the car that intentionally runs her down in the excerpt from the chronicles of the Car vs Feet wars that is Fritz Leiber’s “X Marks the Pedwalk.”

Car Sinister was easy to critique but hard to read. The stories are fantastical, but reading it today, most of them feel cartoonishly old fashioned, especially in the depictions of characters’ families, work, and expectations. In most of these stories, women are either background noise, helpmeets, coveted objects, or overly emotional obstacles our heroes must overcome. The attitudes towards cars and highways—ranging from worshipful and entitled to skeptical and pessimistic—feel contemporary, perhaps because our current climate crisis resonates with the oil crisis of the late 70s.

But even if the editors couldn’t find any car-oriented stories by the many women writing in that era to reprint, the attitudes toward gender, which are unremarked on in the book’s editorial notes, are what truly date these stories and show why most of these writers are truly no longer relevant. Science fiction authors whose work has held up over the years, like Octavia Butler or Ursula K. Leguin, have stayed readable in part because their cultural imagination transcends the “what if it were like now but the cars did cooler stuff and there were bigger guns” style of worldbuilding that the stories in Car Sinister reflect the bulk of their genre in taking on. But in part, too, they hold up because they treat all their characters as fully human, whole people. Most of the stories in this book, and in this genre over the years, fail to do this, and as a result they fail the readers.

Want more feminist science fiction in the world? Back Dragon Bike on Kickstarter through Nov 1, 2019!