Before someone uses my computer to look up a bus schedule or check their email, I try to remember to switch it back to normal. But often I don’t catch them until they’ve begun to type and are staring at the gibberish on the screen in baffled frustration. “Your keyboard is broken,” they sometimes say.

It isn’t broken. I just type funny.

I learned to touch type at 12, and by the time I got to college I was typing constantly. On top of all the papers and emails and instant messages, I had a workstudy gig typing up drafts of a professor’s book and two other jobs that involved data entry. At the end of a week of heavy typing, my fingers and wrists would hurt.

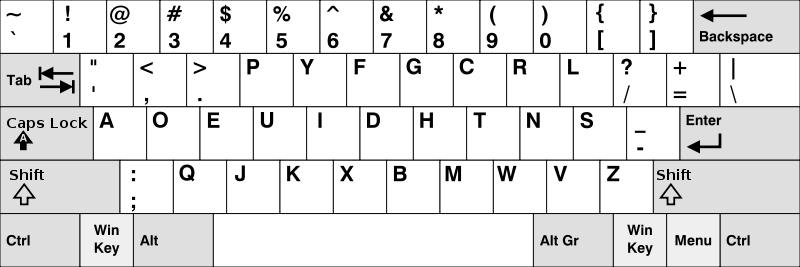

One summer my friend Kelle, who also typed a lot, hacked into a typing tutorial program and we set about learning the Dvorak keyboard layout. I don’t think she stuck with it, but I got obsessed and spent the summer making the transition, typing long pages of hand-scrawled notes at a painfully slow crawl that eventually grew to a respectable speed and finally the fast patter I’d been proud of in years past.

Back in the dawn of typing, there were many different keyboard layouts. The Qwerty layout, which is standard today, was concocted in a fruitless attempt to slow typists down so their sticky old typewriters wouldn’t jam. This meant forcing all sorts of tangled and unnatural finger maneuvers, but competitive typists topped 120 wpm anyway.

Dvorak, on the other hand, was developed to be ergonomic and make typing flow more freely. The ten home keys, where your fingers naturally rest, are the most frequently used letters in English, and key placement is chosen so that punctuation is more easily accessible and the letters in common words are typed by alternating hands. The result: when you type in Dvorak, you don’t need to move your hands as much, and when you do, you don’t need to contort them in the same way.

Learning took three long months — as I gained fluency in Dvorak, I lost it in Qwerty, and there was a month where I was frustratingly slow in both — but my hands haven’t hurt from typing since. (Now it’s my back, but that’s a different story.) And my muscle memory for Qwerty hasn’t left me. I toggled back and forth easily for a few years when I had office jobs, though now it takes some time to get back up to speed when I do need to use it.

I’m not sure why or how Qwerty won out in the end, but I assume it was a similar phenomenon to the way VHS won out over the superior format of Beta, or how pink went from being a boy’s color to a girl’s color — some combination of marketing wizardry, luck, and chutzpah. Meanwhile, everyone who’s heard of Dvorak knows it’s better, but that doesn’t stop it from being relegated to the same brand of fringe wingnuttery as other perfectly reasonable ideas like the metric system, simplified spelling, and ending daylight savings time.

There’s no reason not to switch back over though, now that we’re in the age of the personal laptop. A Dvorak keyboard layout is, unlike road signs or time changes, just a settings adjustment away, and only your closest friends have to know you’re a wingnut. A quick google search shows that there’s even a free program for learning it. And if you want to nerd out about it even more, there’s an illustrated zine about it.

There are a lot of normal, everday things that we take for granted as they wear away at our bodies and spirits. Your keyboard layout is a very small one of those things, but, like riding a bike, it’s one of the rare ones that you can just get down to doing something about. I appreciate that.